1968-71 factory occupation wave in Turkey

Factory occupations and workers’ control in Turkey

In Turkey, there was a relatively large wave of factory occupations and land occupations in the sixties and seventies. In the same years (with the influence of the Yugoslavian self-management model), discussions on ‘workers’ self-management’ intensified and the first workers’ control and self-management experiences emerged: as in the Alpagut Lignite Mines Enterprise in Çorum in 1969, the Günterm Boiler Factory in Istanbul in 1970, and the Yeni Çeltek Mining Enterprise in Amasya in 1980.

Turkey did not encounter militant workers’ actions and factory occupation actions in the sixties. In Turkey, which has witnessed labor movements since the second half of the 19th century, many non-strike actions have been carried out in addition to strikes. Machine-breaking movement, boycotting, damaging employers’ and public buildings, sending threatening letters to employers, and urban riots such as those experienced in Bursa and Uşak are examples of these.

It is seen that the first factory occupation action after the Republic was initiated in September 1934, in a serge factory affiliated with the İzmir Şark Carpet Company. According to the news in the newspapers of the period, the police forcibly removed one hundred five (Vakit, 28.09.1934) or one hundred twenty (İzmir Postası, 20.09.1934) workers who participated in the occupation action from the factory on the grounds of opposition to the Strike Law. According to the news, five of the workers who went on strike on the grounds that their wages would be reduced were referred to the courthouse. The employer rejected the claim that wages would be reduced and announced that it would switch to a performance-based wage system.

Another factory occupation that occurred before the sixties arose from a conflict over working hours in a cement factory in 1948. As a result of the factory occupation action, the employer had to accept the demands of the workers.

The factory occupation action actually started to enter the agenda of the labor movement in the late sixties. There was a wave of factory occupations between 1968 and 1971. The first example of factory occupations in Turkey during this period was the 1968 Derby Tire Factory occupation.

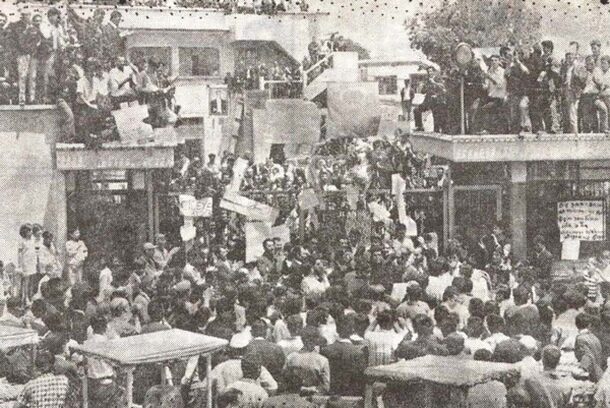

The event that triggered the workers’ occupation of the factory between July 4 and 10 was the occupation of the university by students of Ankara Faculty of Language, History and Geography, and students of Istanbul Faculty of Law, about a month ago. Under the influence of the movement in France and the demand for ‘university reform’ like in France, university youth mobilized in 1968, universities were occupied in June and occupation committees were established. The occupations were only ended three weeks later after the rector of Istanbul University agreed to meet with the students. The occupation action would henceforth be one of the most fundamental struggle tools of both the student movement and the workers’ movement. The Derby factory occupation resulted from the debate on determining the authorized union, and for the first time in the history of Turkey, a referendum was held to determine the authorized union.

In fact, the occupation action in Turkey was initiated by landless peasants before university students and workers. A total of 146 consecutive land occupations occurred between 1967 and 1971.

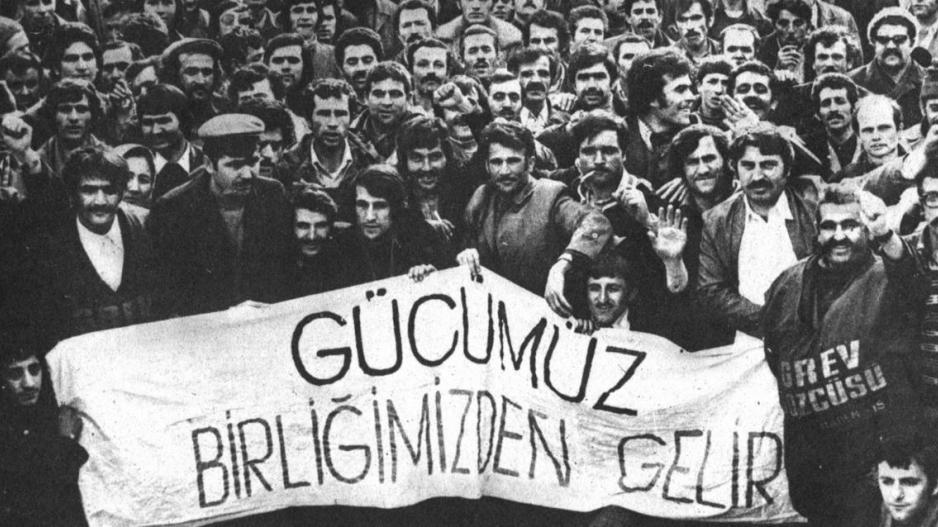

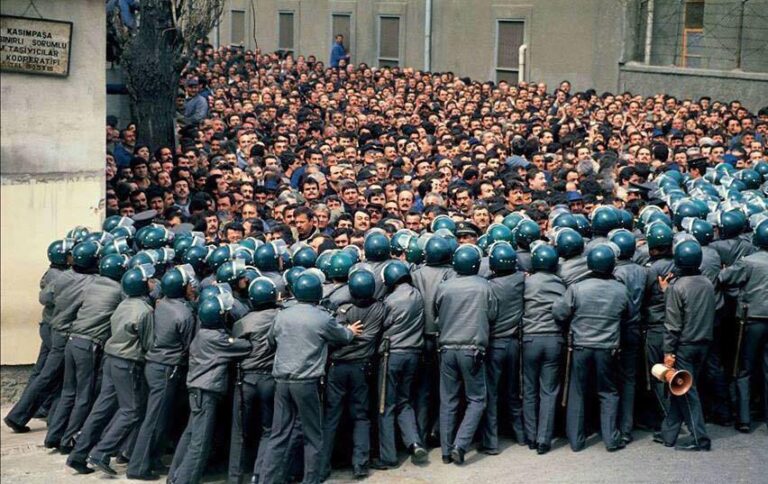

The wave of factory occupations between 1968 and 1971 occurred after the establishment of the new and militant union confederation DİSK. DİSK was founded in 1967 and followed a more combative line, unlike the other confederation (TÜRK-İŞ) with a “non-partisan unionism” approach. Thereupon, employers, the other union confederation (TÜRK-İŞ) which advocates a non-partisan unionism approach and the authorities tried to prevent DİSK. Workers organized under DİSK responded to these obstacles with factory occupations.

It is seen that the unions that founded DİSK led the factory occupation wave between 1968-71. The main reason for all these factory occupations is the violation of union freedom by the employer. Wages and working conditions are also among the demands, but the main issue is the freedom of workers to unionize/organize.

Factory occupation protests were a grassroots movement. In other words, neither any confederation had made a decision in this direction, nor had any union or left party leader made a call in this direction. The occupations were organized by workers and supported by the neighborhoods around the factory.

Factory occupations were generally short-lived. The aim of the workers was not to put an end to capitalist ownership and labor relations, but to ensure that the employer accepted the demands of the workers. However, there were also examples where workers took over enterprises when workers’ demands were not met: As in the Alpagut Lignite Mines Enterprise in Çorum in 1969, the Günterm Boiler Factory in Istanbul in 1970, and the Yeni Çeltek Mining Enterprise in Amasya in 1980.

The sixties were a period when the labor movement was on the rise. In this period, it is seen that, in addition to factory occupation actions, workers’ self-management experiences and discussions intensified. In fact, it can be said that this period symbolically began with the 1963 Kavel resistance and ended with the 1980 Tariş resistance. The Kavel resistance took place during the days when strikes were prohibited in Turkey and accelerated the process of enacting the strike law. The Tariş resistance was a rebellion against the fascist organization within the enterprise and evolved into the armed resistance of the workers and urban uprising. While the Kavel strike paved the way for workers’ struggle in the sixties, the Tariş resistance was the last militant worker action before the 1980 military coup.

+ There are no comments

Add yours