Workers’ control and self-management

Concept of workers’ control and self-management

The terms workers’ participation, workers’ control and workers’ self-management refer to workers’ initiative over the production process. Workers’ participation and control means sharing management between employers and workers. The answer to the question of which side has the initiative depends on the struggle. In management participation and similar models, the company’s strategic decisions are generally made by senior managers, and the influence of employees on these decisions is relatively weak. Workers’ control, on the other hand, emphasizes the power of the workers, as opposed to participation in management. In management participation or worker control, the ownership of the enterprise belongs to the employer (public or private) and workers participate in management in certain ways and levels. However, workers’ self-management is different from these. In workers’ self-management, the ownership and management of the company belongs to the workers. All work/production decisions are made and implemented by workers (not employers or managers). In this sense, it differs from participation in management and similar models and the “socialist” experiences of the 20th century.

Workers’ self-management can be considered as an alternative to capitalist ownership and labor relations on a corporate or macro scale. Capitalist property and labor relations are based on private ownership of the means of production, exchange value rather than use value, hierarchical relations and alienation. However, an economic unit based on self-management operates according to democratic and egalitarian principles; it prioritizes labor and society, not capital and profit. It can then be said that workers’ control is only the first step in the transformation of capitalist relations, while workers’ self-management is concrete experiments with relations beyond capitalist relations. In this sense, workers’ self-management experiences are practically a critique of capitalism and a search for a new production/society relationship.

Workers’ control and self-management in history

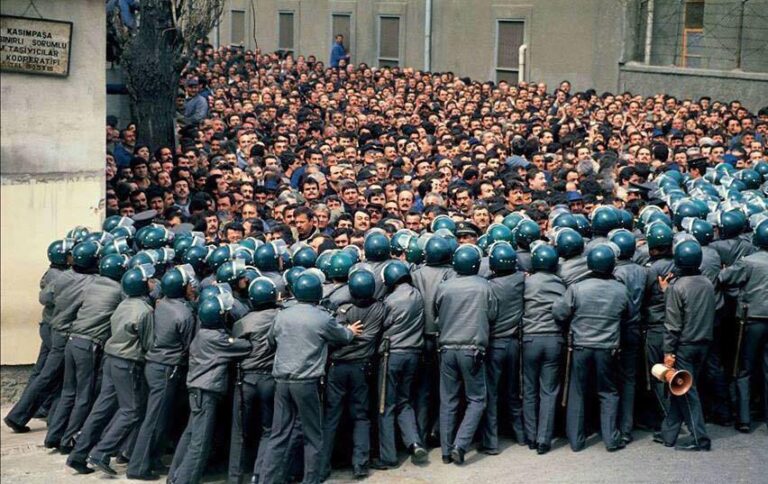

It is possible to find many examples of workers’ control and self-management throughout history and today. For example, the Paris Commune of 1871 can be seen as the first experience of workers’ self-management in the history of modern capitalism. The councils and committees that emerged in Russia, England, Germany, Italy and other countries in the first quarter of the 20th century are also very important experiences. During the civil war in Spain between 1936 and 1939, self-managed production reached an enormous size, especially in Catalonia. Yugoslavia and Algeria after the Second World War, France and Italy in 1968 and 1969, Portugal after the 1974 Carnation Revolution, and Iran in 1979 are among the examples where self-government experiences and/or discussions came to the fore. In Britain, for example, in the 1970s hundreds of factories were occupied by workers and brought under workers’ control, and the Institute of Workers’ Control (IWC) was established to conduct research into workers’ control. Again, for example, in the same years, the experience of the LIP watch factory became the symbol of workers’ self-management not only in France but all over the world. Throughout the history of modern capitalism, it is possible to come across numerous examples of initiatives that can be considered within the scope of workers’ control and self-management.

Workers’ control and self-management today

Today, debates about workers’ control and self-management are being revived. Behind this resurgence are experiences of worker control and self-management in Latin America.

Important examples of workers’ control and self-management can be found in Latin America, particularly Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, and Venezuela. In these countries, many companies that were at risk of bankruptcy in the 1990s and 2000s were taken over by workers and turned into self-management. In particular, the 2001 Argentine economic crisis was a turning point. During the 2001 crisis, workers continued production in many factories that went bankrupt in Argentina, and democratic and egalitarian relations were established in these factories. Interestingly, similar examples continued to be seen in some factories in the years following the 2001 crisis.

In Argentina, these enterprises are called “empresas recuperadas”. The term “empresas recuperadas” refers to factories/enterprises that are taken over by their workers and continue production due to bankruptcy and/or abandonment by the employer. These factories/enterprises have been transformed into worker cooperatives and operate according to democratic and egalitarian principles. Latin America stands out on the issue of producer self-management, with social movements known as MST (Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra) and ERTs (Empresas Recuperadas por sus Trabajadores/as). MST and ERTs are at the center of Social and Solidarity Economy discussions and practices that have developed in recent years.

Today, in other countries, initiatives called “workers’ democracy”, “workers’ economy”, “social and solidarity economy” are attracting attention and developing. These experiences and discussions are important as a reflection of the search for alternatives to the neoliberal model and capitalist relations.

+ There are no comments

Add yours